Get busy livin' or get busy dyin': Thoughts on 'The Life of Chuck'

Mike Flanagan's latest Stephen King adaptation is an uplifting tale about the inevitability of death

I cross my thumbs left over right whenever I clasp my hands together (never right over left). My face contracts into the same frown as my dad’s does when I see something I don’t like.

I started listening to Cross Canadian Ragweed because a high school girlfriend showed me the music video for “17.” I chose a career where I could write because an elementary school teacher told me I was good at it. I’ve developed a budding love of Broadway musicals because Taylor sings show tunes around the house constantly.

I now work part-time at my local comic book shop because an old colleague introduced me to “Locke & Key,” and I started reading comic books as a result. My affinity for dumb action movies comes from lazy summer afternoons on the couch with my brother. I enjoy the ritual of cooking breakfast (when I get up early enough or have enough time) because it reminds me of my grandfather, who never met a form of egg or bacon he didn’t like. I think of my other grandfather every time I hear a gospel song.

Some of those markers of my personality are inherited traits, generational genetic hallmarks that probably date back centuries. But most of them are the result of the impact of other people on my life. I am who I am, and my inner life is as rich as it is because of all the people I’ve met.

I am large, I contain multitudes.

But if I contain multitudes, then so does everybody else. And isn’t that wonderful? This is the point of “The Life of Chuck,” the audience-award winner at the 2024 Toronto Film Festival, out now in wide release from Neon.

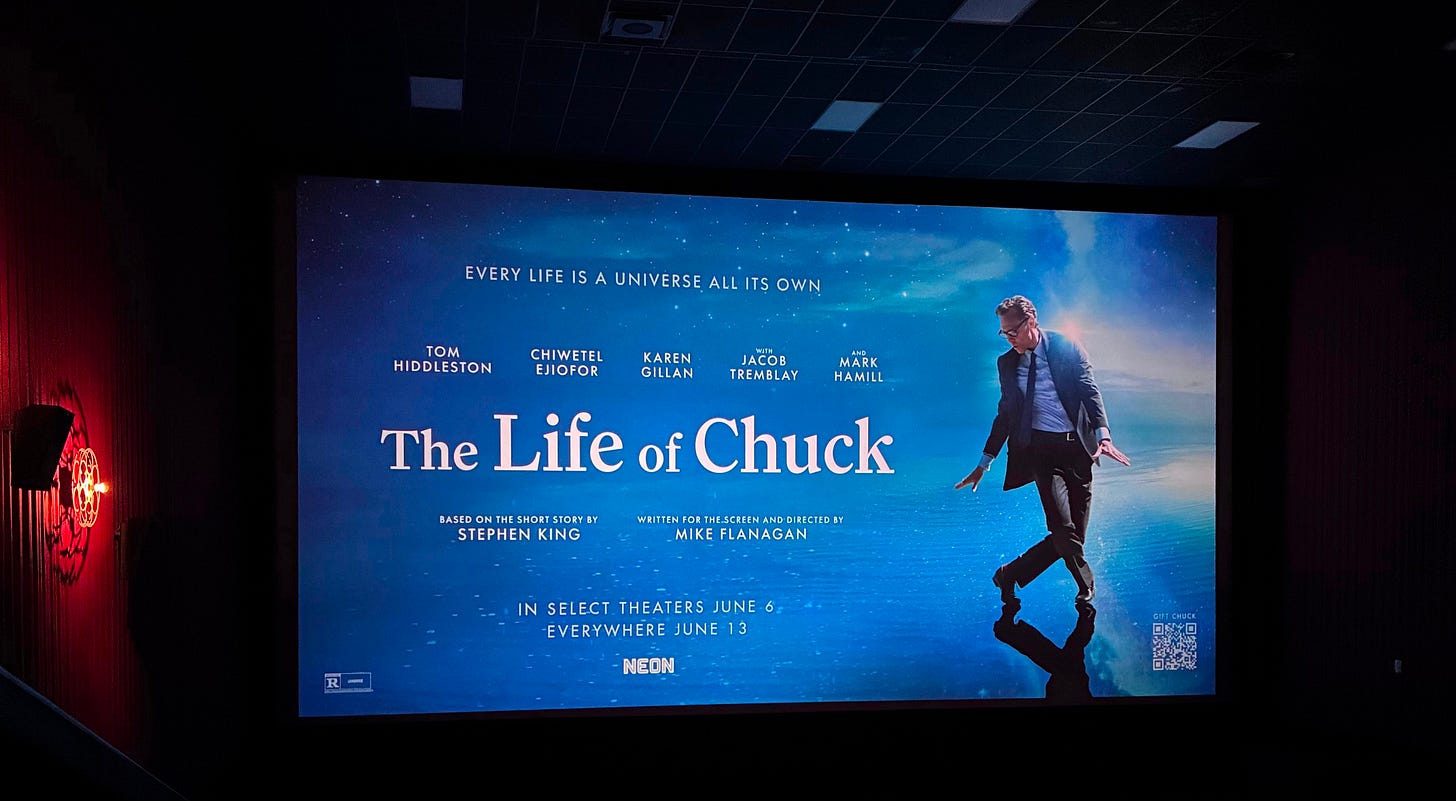

Director Mike Flanagan’s earnest adaptation of Stephen King’s 2020 novella examines the worlds that we each create through our experiences. It follows the life of an ordinary man named Charles Krantz (Tom Hiddleston) through three acts, told in reverse chronological order.

The New 'Life of Chuck' Trailer Is Here, And You Will Cry

Stephen King and Mike Flanagan fans, rejoice! We are one day closer to the release date for Flanagan’s film “Life of Chuck,” adapted from King’s novella of the same name.

It’s a faithful adaptation — sometimes too faithful. I could have done with less voiceover narration and thought the final moments would get trippier than what was on the page. The two monologues that Flanagan wrote specifically for the movie were beautiful authorial stamps that the film needed more of.

But if you’re a fan of King’s folksy side (think “The Shawshank Redemption,” “The Green Mile,” “Stand By Me,” Hearts in Atlantis,” the “‘Salem’s Lot” interludes, multiple short stories) and/or Mike Flanagan’s monologues about matters of the soul (“The Haunting of Hill House” and “Midnight Mass” especially), you’ll find a lot to love here.

Note: It’s hard to fully talk about this movie without spoiling everything. So consider this your spoiler warning. If you haven’t seen the movie yet, go watch it and then come back.

The story starts at the end, with Act III: Chuck is dying. Therefore, his world is dying — “When an old man dies, a library burns to the ground,” as the proverb goes.

The movie takes a bit to explain what’s happening in Act III, which primarily focuses on a high school English teacher named Marty Anderson (Chiwetel Ejiofor). He’s struggling to deal with his work when it seems like there’s a new catastrophe every day. California is falling into the ocean. There’s a new weather disaster with each news report. War and famine are breaking out everywhere.

And through it all, people start seeing random billboards pop up all over town, showing a middle-aged accountant and the slogan “39 GREAT YEARS! THANKS, CHUCK!”

As Chuck wastes away at 39 years old from brain cancer, the world he created in his mind starts to devolve as well, which means the end of the world as Marty knows it.

The entire first segment (especially its final few minutes) feels a lot like a “Twilight Zone” episode. It’s helped along by voiceover narration by Nick Offerman, who’s doing his best arched-eyebrow impression of Rod Serling.

For all the apocalyptic imagery in Act III, the characters find a way to stay optimistic in the face of annihilation. Marty and his ex-wife Felicia (Karen Gillan) reunite, and wager that when presented with the end of the world, most couples would opt for marriage instead of divorce. They spend their last minutes together holding hands, watching the stars go out as Chuck, who we finally see in a hospital bed at the end of Act III, takes his final breaths. Moments of melancholic joy living in harmony with catastrophe.

Cut to black.

Acts II and I continue to work backward through Chuck’s life. Tom Hiddleston plays Chuck in his late 30s as an accountant who is suddenly moved to dance to the beat of a busker’s drumset one afternoon, and Benjamin Pajak later plays young Chuck, who learns to dance from his grandmother (Mia Sara).

The crux of the movie is the extended dance sequence in Act II. Chuck doesn’t know he has months to live; he just knows he gets bad headaches sometimes. He’s an accountant, like his grandfather (Mark Hamill) before him, but his childhood passion was dancing. He hears the groove and stops in the middle of the street. Here, Flanagan inserts a blink-and-you-miss-it flashback to his grandmother dancing in the kitchen.

That moment has caused me to well up with tears every time I’ve seen it. It happened when I saw the trailer, when I saw the movie for the first time and again the other night when I saw the movie a second time.

If Act III is about remembering the people who have shaped us, then Act II is about how little moments each day cause us to remember them, and how we shouldn’t push those memories away — we should honor them. In Chuck’s case, he acts on it.

He gets a foreboding headache midway through that dance sequence (much like Act III, a moment of joy commingling with a coming catastrophe), but that doesn’t stop him from inviting a young woman (Annalise Basso) to dance with him.

The sequence is earnest and whimsical, and Flanagan films it as an homage to the musical films we see young Chuck watch with his grandmother in Act I. (I especially liked that the dance sequence is light on the quick-cutting editing style that a lot of musicals use now; we actually see wide shots of Hiddleston and Basso dancing.)

The two of them enthrall the crowd and help the street busker make more money in a day than she would in a week. And thus, by remembering his grandmother, Chuck crafts a moment that the crowd of onlookers might recall in a time of trouble, or serve as their reminder to live life to the fullest. As the crowd disperses and the day ends, the camera pans out, and we see some characters in the background who were principal players in Act III. It’s a clue to understand what’s happening in Act III, but it’s also making the point that just as those people somehow got tucked away in the recesses of Chuck’s brain, so too will he for the dozens of people who saw him dance that day.

In that way, we are all large. We all contain multitudes.

Act I goes back even further, to Chuck’s early life. Again, it is a tale of great sadness mixed with great joy. He lives with his grandparents because his parents and unborn sister died in a car accident when he was young. His grandmother teaches him about the art of dancing; his grandfather teaches him about the art of math. Both have a huge impact on how he sees the world.

This section of the movie is the most stereotypically “Kingian” of the story. Chuck’s grandparents’ old Victorian home has a haunted cupola, which was hinted at earlier in the film but is now shown in all of its glory. Chuck’s grandfather says the room is “full of ghosts”; he swears he saw the deaths of two of their neighbors before they died. And he says he saw how his wife would die. As such, the room is locked up.

Chuck becomes fascinated with the cupola at the same time he becomes fascinated with dancing. He’s good at it, and even teaches his classmates a thing or two. The film’s second dance sequence features young Chuck in a gym at a middle school formal. Here is where more characters from Act III come in — Marty and Felicia are chaperones.

This dance sequence is punctuated by, again, joy and sorrow.

Ecstatic and riding high after his performance, Chuck leaves the gym. He starts dancing around the football field, and in all his movements, he cuts his hand on a chain-link fence. Life is joy and life is pain, often in the same couple of moments.

The movie ends with Chuck finally taking a look in the cupola just before he moves out to go to college. He sees himself, older and wasted away in a hospital bed, hooked up to a machine. Unlike his grandfather, he decides to embrace his vision instead of being scared of it. He quotes Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” at the end to solidify his decision to never forget what he saw. He vows to keep living his life until he can’t anymore. He could have just as easily reached back into another King story to make his point: “Get busy livin’, or get busy dyin’.” We’re all going to die someday — would knowing the method or the date change the fact that we should embrace life, and therefore, allow others to embrace theirs?

And what “Life of Chuck” argues is that while the universe is large and contains multitudes, it also contains you. It further argues that a quiet, “normal” life is still an honorable, exciting life. Look at all the worlds everyone has inside them every day, full of people and experiences. To quote another Mark Hamill character, no one’s ever really gone if you can remember them, and remember them well.

More than a trite reminder to “live each day to the fullest” or to “dance like nobody’s watching,” “The Life of Chuck” is a testament to the power of memory and the value of our impacts on each other — and it’s often the little moments that add up to a life that we’ll remember the most at the end.

“The Life of Chuck” is in theaters now.